Uta-garuta

There are a lot things I don't generally want to do on New Year's Day, and one of those things is: desperately try to remember a hundred short poems while occasionally trying to grab something off the floor as quickly as I can.

Which is fine, nobody asked me to. But there's a game that asks its players to do exactly that - Uta-garuta, a Japanese game traditionally played in the first few days of the new year. So now it's 2 January, there's still a few days left to run in the Uta-garuta season (the Japanese championship is on 7 January), and GOSH it sounds like an interesting game.

It's played with a deck of cards that show 100 different five-line poems (from an anthology called the Hyakunin Isshu, which is around eight hundred years old). Each poem is split across two cards - the first three lines are printed on one card, and the last two on another. The hundred cards with the poems' openings are the reading cards; the cards with the ends of the poems are the grabbing cards.

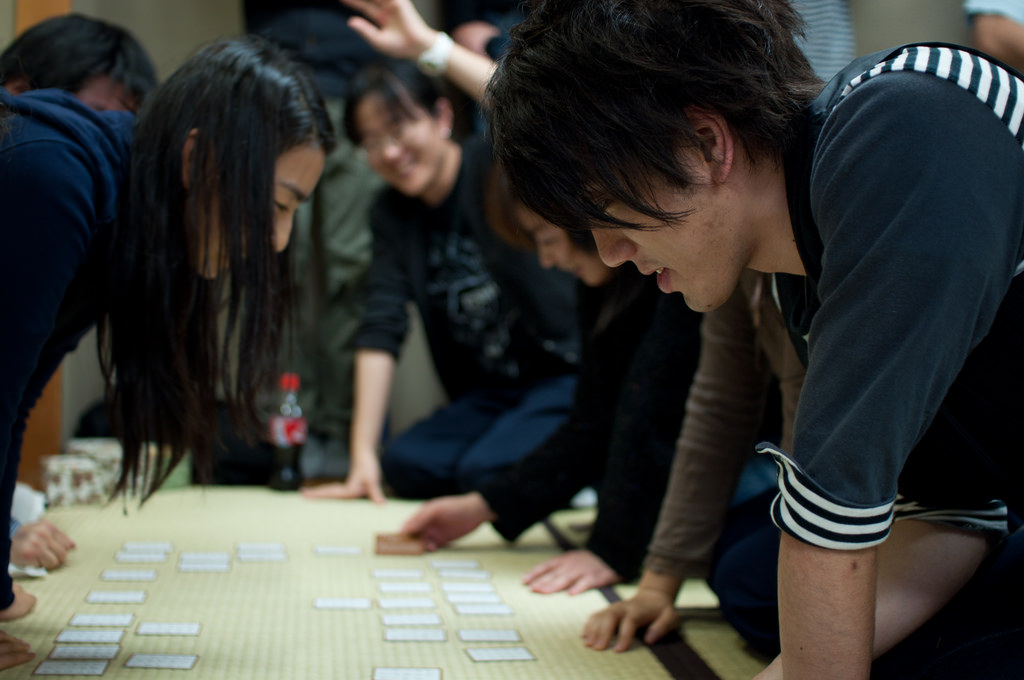

And those card names, reading and grabbing, go a long way towards explaining how the game works. You lay out the grabbing cards on the ground, face up. A reader selects a reading card at random, and reads it aloud. All the players race to spot the card that finishes that poem off and to, well, grab it.

It's a game that grew out of simple matching games - you know the sort of thing, flip over two cards and try to find a pair. But as matching games go, it really takes the memory aspect and runs with it. On a grand scale across games, it asks players to remember the 100 poems perfectly. Expert players can identify a lot of the poems just from the first couple of syllables:

"...In seven of the poems, the first syllable is unique to the set of one hundred, and thus enough to identify the poem. The explosion of activity comes as soon as the first sound is out of the reader's mouth. But for all the rest of the poems, the players must wait until the first unique syllable is spoken, and in some cases, this may be as far into the poem as the sixth syllable. In the example we saw earlier, 'Naniwa gata ...', the players had to wait until the 'ga' was spoken to distinguish the poem from a similar one which starts 'Naniwa eno ...' But of course, if that 'other' poem has already been taken, one need not wait that long, so it is always necessary to keep mental track of which cards have been removed from play." (David Bull. "Karuta: Sports or Culture?")

This description points at the simultaneous feat of short-term memory the game demands. It's not enough to know all the poems. You also have to keep track of which poems have already been read aloud in a particular game - and where all the different grabbing cards are located. In competitive play, there's a fifteen-minute session before the game begins to allow everyone to try to settle the incidental random layout of cards for this particular match into their heads.

It's also a surprisingly physical game, as videos demonstrate. As long as you touch the right card and move it out of the playing field somehow, it doesn't matter if you grab it or flick it, or if you knock other cards out of the way. Players just pick up disarranged cards afterwards and put them back in place. So competitive practice involves flicking cards all over the place.

There are two standards ways to play. In the more casual version of the game, you start by spreading out all the grabbing cards. A reader reads from the reading cards, and three or more players try to grab the right ending card. Whoever has most grabbing cards at the end of the game is the winner.

The other way to play is more serious, a two-player (or two-team) variant used in competitive matches - including in the national championships that will be taking place on the 7th (it looks like it'll be streamed live - free registration required).

In this version of the game, each player lays out 25 grabbing cards in front of them, in their territory, so there are 50 on the floor all together. A reader reads aloud - using the whole deck of 100 reading cards, so for some opening lines there just won't be a matching end card available.

If there is a matching end card, players race to touch it first - regardless of whose "territory" it's in (though if they tie, whoever's territory it's in takes priority). If you win, you take the card and remove it from the board, and then move a card from your territory into your opponent's. The first player to clear their territory completely wins.

It's a traditional New Year's pastime, with friends and family playing together for fun around 1-4 January, and the national championships a few days later. So it seems like the next couple of days would be a good time to try it out. But for all that there are print-and-play versions available for free online, it's a hard game to have a go at if you don't know Japanese (which I definitely don't). And that's even before you even get to the bit about having to know 100 poems by heart.

Still, no need to despair. There are plenty of card games that are variations on that core listen to someone read, grab a card quickly mechanic - it's not just used for the classic poetry game. There's a version of the game with 48 Japanese proverbs, for example, for children. There's even a version where you're trying to identify particular monsters and grab them.

So it should be easy enough to try out that core mechanic, even if I can't play the game itself. The simplest possible version is probably something like...

Grabble

To play Grabble, you'll need four or five players and a load of blank cards or post-its or scraps of paper.

Everyone should write 12 different common phrases or sentences, split across different scraps of paper. Try to use one colour for the openings, and another for the endings. Pick sentences you think the other players will know: phrases, quotations, lines from songs, catchphrases from television shows you all like, weird private jokes - whatever. A ROLLING STONE // GATHERS NO MOSS. TO BE OR NOT TO BE // THAT IS THE QUESTION. TWO HEADS // ARE BETTER THAN ONE. If you can think of a few sentences that start with the same sound or two - like "to" and "two" above - then all the better.

Now, lay out all but five of the sentence endings on the floor or on a table, and put all of the openings in a bowl or a hat.

Pass the bowl around. When it reaches you, grab a scrap of paper and read it aloud. Read very slowly! Give people lots of time to respond.

Everyone else has to race to grab the appropriate ending - unless the sentence is one that they added, in which case they can't play for this round. If a player grabs the wrong card then they have to give up one of the cards they've already grabbed.

When all the cards on the table are gone, count up who grabbed the most. They're the winner!

If you play again, use the same cards! The better you know the phrases, the more tense the game is likely to get.

More about Uta-Garuta (in English)

Sports Japan has a half-hour episode about the game, explaining the rules and talking to champions. And there are a ton of competitive matches on Youtube.

World of Kyogi Karuta has a TON of information, including stuff like an explanation of what counts as a foul in the game.

Karuta: Sports or Culture? by David Bull has a great description of a competitive match, and an overview of the game and its history.

A blog post, "Poetry in Motion", about the training process and skills involved.

There's various translations and versions of the hundred poems online, but this one (from the University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center and the University of Pittsburgh East Asian Library) seems particularly clear.